It's not all about Donna

Another Memoir as a Short Story contribution. This one has a trigger warning. I struggled to finish this piece once I realised this memory was not all about Donna. Names have been changed.

The school bell for the break will ring any minute. I can tell because Miss Crouch is rounding up the lesson. It’s Donna’s turn to read the next line of the poem, Jim, by Helaire Belloc:

“Ponto!”, the keeper shouted with an eager frown. “Let go, sir, down sir, put it down!”

She won’t cooperate and we all know it.

“Come on now Madonna, give it your best,” chides Miss Crouch. “You just need to shout. You can do that can’t you?”

Why does Miss Crouch persist? Donna sits spoiling in the heat of the biting Adelaide sun that streams onto our backs from the classroom window and Miss Crouch pokes and pokes at her until she pops. There is so much flesh to Donna, her olive-toned skin fit to burst over a shape that is one of a woman’s not a girl's. I fear she will explode and I, the only one who dares to sit near her although she has a desk to herself, will be covered head to toe in the blood and guts of the Madonna.

We are the same age. How can that be?

My whole length fits snugly on the back seat of our car, a place I like to stretch out to sleep during long drives on the Australian freeway. Tucked up with a pillow and blanket below the view, I don’t think about forest fires engulfing us. I love the motion of 80 mph on an open road, not even a breeze although Dad has his window right down. The sound of a kookaburra’s call, or parakeets announcing “coming through” passes overhead, and everything is calm and in the now. It was a two-day drive, starting at dawn each morning, from our home in Melbourne, Victoria to here.

“Kangaroos Ni!”

I take a peek. There’s nothing left to look at but a dead tree and a cloud of red dust as the large roo’s bound off back to the desert - the branches of the tree reaching out mid-scream, one left hanging, like a broken arm, snapped at the elbow. But then I see a wallaby snuffling and licking at its trunk, white as the Canadian snow. And the view is gone, and I return to my cradle.

And yet.

The Salvation Army officers we swapped houses with who took the same route to Melbourne never made it. They made the first stop, a sleepover at another Army officer’s house, the one that had been our last stop. After setting off for the final stretch of the journey, they were suddenly car-jacked by escaped prisoners and shot dead; one in the car, the other trying to escape. I’ve searched the internet for official news of this story but have never found it, but I know it to be true. I remember the noise of the unsaid before the telling; I’m familiar with that. (The unsaid is what the adults aren’t saying.) I was upset that they’d never meet the five tall trees at the end of our old garden, and watch them laughing and dancing together in a Melbourne storm.

My friend Terry Moon Face (my nickname) from school has been out to the bush and the desert, with his folks. He went on a quad bike! How jealous am I? He smiles back at the world, whatever it throws at him and most of the time the culprit is Miss Crouch. He is currently on a punishment regime that involves putting the chairs up on the desks at the end of the day and coming in early to put them down again. I am helping him because I think it’s very unfair. He tells me everything whizzes past him in swirls and squiggly lines and leaves trails, or shadows that explode over his head and fall onto him so that he can’t breathe. The dust gets into his eyes, ears, nose, and mouth and he coughs and spits and Ms Crouch says “He’s playing up. Ignore him everybody”.

Miss Crouch says no one else will sit near Donna or Terry, except for me because I’m a Christian girl, the same as herself. I didn’t know I had a choice. I recall feeling very distressed that I was similar to her. For a month I sat outside her house every Saturday morning, wanting to knock on her door and ask her what exactly was the same about us; but I couldn’t put it into words. I’m 9.

According to Australian immigration, Terry is a white Australian, Donna is a white European Australian, and I am British, the only one in the school to arrive here by aeroplane. The world is made for me. I’m familiar with the type of English children’s literature we read its scenes and settings. No one knows why the hell Jim went to the zoo, whatever that is, with a nurse. The poem doesn’t say he was sick. It’s even harder if English/Australian is your second or third language.

Donna is Greek and only speaks English at school, although she is often absent, like Terry Moon Face. She always says she is helping with the harvest whatever the time of year. She smells of the earth and grapes. When she is not present I breathe a sigh of relief because I don’t have to steel myself all day for the Madonna’s emotions to make their urgent escape. Perhaps the whole class feel the same about her and Terry.

Moving from modern Melbourne and a private school with nice spotty smocks for art to Adelaide, a State school, with one tree in a concrete playground full of different languages, Cypriot, Italian, English, Maltese, and Turkish is a lot of change to handle when you're nine. And then there was Donna, who stood under that tree every breaktime, peering out disdainfully at us and our childish games from behind her too-long fringe, her brunette locks falling like an expensive fabric over her shoulders. Her pain unnerves me.

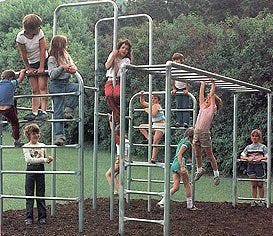

The playground apparatus was at the far end of Donna which was the motivation. Terry Moon Face and I go in and out, in, out, in and out at speed, around a line of staggered poles like dogs in agility, holding our sandwiches. After that, we swing back and forth across the monkey bars. I jump down and venture up the bars combo using a rope ladder, one, two, three, I’m at the top, around 10 feet high. The steel is hot from the sun, almost too much to the touch.

“Hey everyone!” I shout clinging on with both hands to the burning metal.

And down again as quickly as I can.

“What can you see?” asks Terry.

“A fence,” I reply. “I’d have to sit up there to see anything.”

And that was it. I was back into searching for this damn horizon, every break time and lunchtime play. A horizon point that doesn’t exist, like the pot of gold at the end of the rainbow because that is where my mum is, waiting, not next to God with grandpa like they say. And in all truth, I did secretly worry about making it back without characters like Mary Poppins around in Australia, but there’s still the thought that my mum is there and we are always ‘nearly there’, never here, aliens wherever we plant ourselves. I didn’t tell Moon Face. He doesn’t know my mum is dead because I’ve got a new one.

Next break time I’m determined to sit on the top rung but it’s too hot for children to go outside and play, and I’m left playing Monopoly with Terry, Donna, and Miriam, a new girl that’s just started. It’s only a matter of time before Donna upends the board and everything on it. What will Miriam think? I’m practically taking everyone’s turn for them, and even speaking for them sometimes - it’s not much different from playing school at home with my toys.

My parents got a letter saying how lovely I am because I offered to sit next to Mariam. I felt it was a fresh start from sitting so near Donna and sharing a desk with Terry Moon Face. Miriam is an aboriginal who speaks no English and wears oversized middle-aged ladies' summer dresses. My heart aches when I catch her eye, my whole being wants to give up and sit my life away.

I’m furious with Mis Crouch, absolutely fuming although I still don’t fully understand why, it just makes sense that this is an idiot comment, and am marching like a good soldier to school the next day determined to have my say. In the end, I blubber about Jesus and I believe, there was mention of “creatures great and small” so all I did was prove her point. I’m a wee colonial bastard.

Eventually, I can show you the red-raw burning skin behind my right knee and the accompanying bruised thigh from the daytime practice on the high bar. I am determined to do a full rotation with one knee cocked over the bar, me holding tight to my ankles.

“You have to go faster to get your speed up,” shouts up Terry, who won’t join me because he says the noise of the sky is deafening.

One full rotation took three break times, but by the next one, I managed two complete turns. More confident now I can stop to look out over the school fence as long as I like. I can eat my curried egg sandwiches up there. There is no distant horizon beyond the smog and buildings, the patch of green of the park sometimes flashes like a jewel in the grey. The main view is the backyard of a faded wooden yellow house with green trimmings that have peeled away to leave the wood, mousy brown like Terry Moon Faces hair. There’s a patch of dusty ground on which sits a broken barbecue and an old car back seat, torn and dirty. Empty cans litter the ground. A rotating washing line stands forlorn in the back corner. Yellowing grass making its escape through the cracks of the pavement that lead from the back door to a too small for a shed wooden construction. It’s an outside toilet. My stepmom’s mum, poor and blind living on long-beaten farmland somewhere here in Adelaide has one. Someone’s is in there! I scuttle back down quickly.

“Someone’s there!” I shout at Terry. “I think I was caught watching someone go to the toilet. They’re going to come and tell the school! What are we going to do?

Terry shrugged.

The next day he was there again. And the next.

“That man is still there, in the toilet,” I tell Terry.

“Don’t look then,” Terry responds impatiently. “Does he see you?”

“No. He just goes out the back door to his toilet by the fence and shuts the door. I’ve never seen him come out.”

Terry still hasn’t made it to the top bar and I’m on a strict promise not to tell anyone, especially his mum and dad, who are Hells Angels. This means nothing to me but I can appreciate it’s not a popular fact. Instead, I appreciate he has an understanding of certain things that come from being in a church or other group, and adults belonging to my friends, I take them at face value. I’m 9.

I stay away from the bars until Terry Moon Face bets another boy I can spin from the top one. I don’t know what a bet is and resolve to ask an adult later.

The man comes out, goes into the toilet and leaves the door open. I try not to look, which means I fail. I climb down as soon as I see Terry Moon Face shake hands and collect an enormous and most beautiful marble; from up here it glints and sparkles. Once I’m at the bottom he hands the marble to me: “For you,” he says.

I don’t have Terry to myself until it’s time to put the chairs on the desks at the end of the day. The minute Miss Crouch leaves the room saying her usual “I’ll be back in a minute,” I “Psssst” and declare I saw “that man’s bottom. His trousers were around his ankles.

“And he turned around and was doing something funny,” I continue. “I’m in such big trouble.”

Terry is silent. I think I'm in trouble with him. We finish the chore and leave before Miss Crouch returns. It’s always like that. She probably never comes back to check on us. Terry walks me home, leaving me at the front door and saying “You’ve got your marble haven’t you?”

“Yes,” I say, and take it out of my pocket to show him. Off he skips, hands in pockets with his Moon Face and straggly shoulder-length unwashed hair, not turning back. I’m wondering if I told him anything after all.

I tell no one else. Not even my neighbour Karen who I talk to at bedtime in our tin can with string telephone draped between the sides of our houses and adjoining fence. She will tell her big sister and then her brother, and then they will be mean.

After the weekend, we discover the top end of our playground is blocked off. The house owned by the man in the toilet is burnt to the ground. Our school fence is down. The stink of burning and the dust of ashes make their way to our morning lineup outside the building, Did it happen on Friday or Saturday? Is it true they rescued a mistreated German Shepherd and three cats? How many fire engines were there? Someone says the man who lived there is dead. Someone else says he was arrested. And where is Terry? He’s standing still and quiet in the line watching and waiting for me to see him beaming like a harvest moon.

“Why are you in such a good mood,” I ask. “You hate school?”

“Because I’m free of my sins,” he says grinning. “I admitted to them that I was too scared to climb to the top bar like you,”.

“Your parents?”

“Yeah.”

“They weren’t cross, were they?”

“No. Not at me,” he says. “And my dad says you’re just the type of girl I should marry - when I’m grown,” he says, folding his arms and smirking.

“I’ll probably be in a different country by then,” I respond. He “Huh’s” with resolve, unfolding his arms.

“Are you helping,” he says, heading off to the classroom to put down the chairs. “Of course,” I say, rushing to catch up.

The next day starts as the last and the next, with the smell of rising yeast, from the bakery around the corner, and the sun shining brightly until the land burns. It never rains here. In this white wooden house, there’s a long and wide black-and-white tiled hallway leading from the front door to the back. I love it. There’s a big old washing press in the laundry room next to the backdoor and a Butler sink. Out the back door, you’re under a wooden overhead terrace that groans from the weight of an established old white grape vine. I raise my arms and a whole bunch fall gently into my outstretched hands, so heavy and glad to be free. The world was made for me.

This piece is available free for 7 days to inspire comments before it’s removed for submission elsewhere. Thanks, everyone.